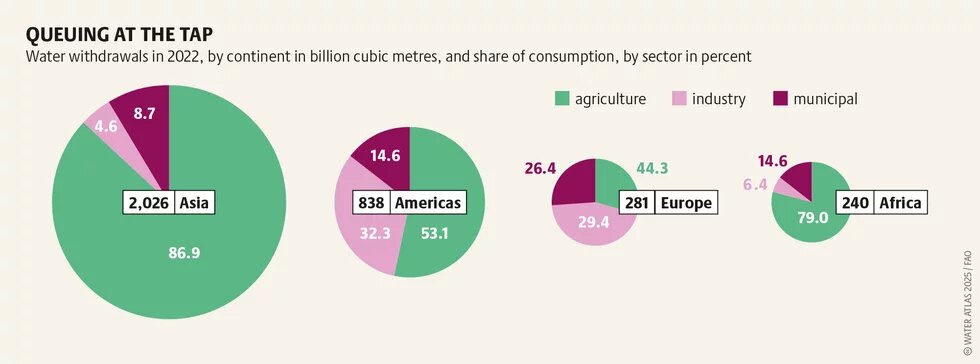

Agriculture is the single largest industrial sector when it comes to consuming water: 72 percent of the world’s freshwater consumption is used to produce food. Ensuring a secure supply despite the threats posed by the changing climate will take political will.

Every year, almost 3,000 cubic kilometres of water are extracted for agriculture from the world’s groundwater reservoirs, lakes, and rivers. The share of water used by agriculture in total consumption varies depending on the region and income level. In high-income countries, about 40 percent goes to farming; in low-income countries up to 90 percent. Some 3.2 billion people live in predominantly agricultural areas where water is either scarce or very scarce. Many of these people are small-scale farmers, who play a key role in producing food and ensuring food security.

The world’s irrigated area has more than doubled since 1961, according to the United Nations. Around 20 percent of the global cropped area is now irrigated, and this area produces 40 percent of the world’s food. The increasing demand for irrigation is the result of the rising population. The situation is exacerbated by weather extremes such as long droughts, which are becoming more common because of the climate crisis.

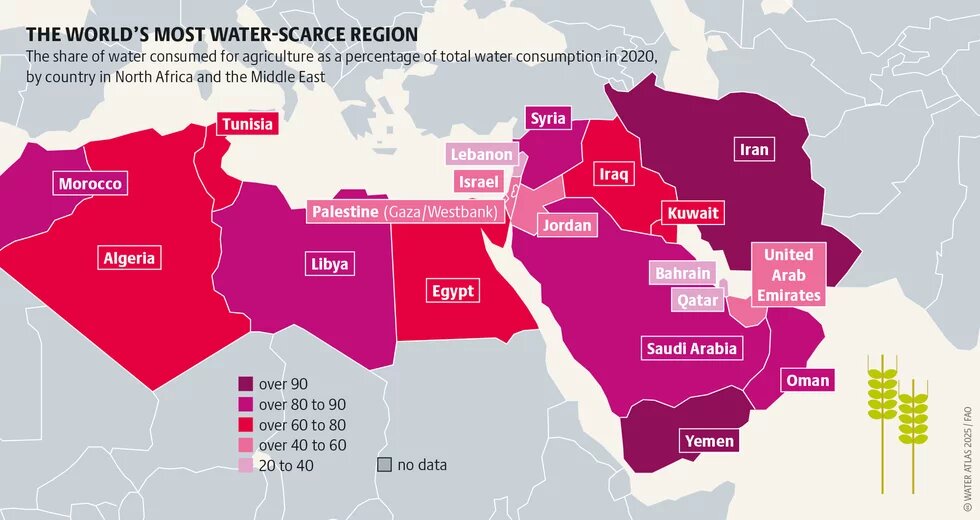

The Middle East, North Africa, India, northern China and the southwestern United States of America are especially hard hit by water scarcity. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that the demand for water for irrigation could double or triple by the end of this century. Projections show that the rising demand for irrigation, combined with the higher evaporation caused by the climate crisis, will ultimately increasingly deplete groundwater reserves by the turn of the century.

In Punjab, India’s breadbasket, the groundwater level has fallen by as much as 40 metres in the last 30 years. Just 1.5 percent of India’s total area grows 20 percent of its wheat and 12 percent of its rice. But four-fifths of the usable groundwater is used to irrigate these and other crops. The rising costs of irrigation due to ever-deeper wells drives farmers into debt. According to a study by the Indian Council of Social Science Research, around 86 per cent of farming households in Punjab were in debt in 2017.

The agricultural sector consumes less than one-third of the water used in the European Union. This proportion is much higher in some countries; for example in Spain it is 82 percent. Both surface and groundwater there are especially polluted. The situation in France and Italy is similar. Germany is one of Europe’s most water-rich countries, with an average of between 700 and 800 litres of precipitation per square metre each year. But even here, an increasing share of the cultivated area is irrigated, especially for growing vegetables. Between 2009 and 2022, the irrigated area grew by almost 50 percent, from 372,700 to 554,000 hectares.

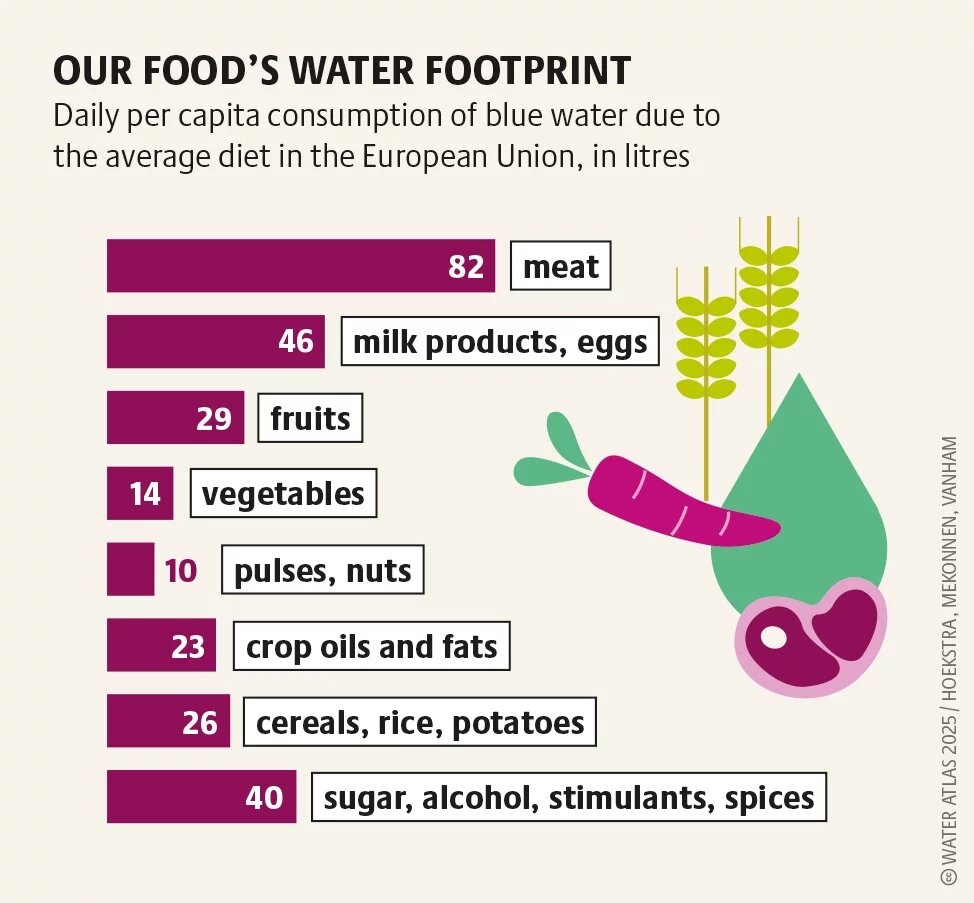

Virtual water is the amount of water needed to produce the products – and especially the food – that we consume. Many Global North countries have high consumption levels. For example, Germany consumes 219 billion cubic metres of virtual water per year – almost five times the volume of Lake Constance, Germany’s largest lake. But only a small proportion of the virtual water consumed in Germany comes from Germany itself. Around 86 percent is imported in the form of irrigation-intensive agricultural products grown abroad, such as fruit, nuts, rice, and vegetables. Two factors need to be taken into account when scrutinising the water consumption of a food product: the amount of water needed to produce it, and the water availability in the region where it is grown. This combination is used to calculate the item’s scarcity-weighted water footprint. The scarcer the water in the growing region, the larger the footprint.

Forecasts show that water stress in the European Union will increase by 2030, meaning that available reserves will be less and less able to meet demand. To provide coming generations with a secure water supply, it is necessary to critically examine how we currently use irrigation for agriculture.

Farms and agricultural businesses play a key role in water management. They can protect water resources and respond to the climate crisis by using rainwater, planting adapted crops, using cultivation methods that limit evaporation, protecting the soil, and combining trees and shrubs with crops in agroforestry systems.

That will require financial incentives, such as water-related agricultural subsidies. The European Union could support resource-conserving measures through its Common Agricultural Policy to a much greater extent than it does now. Instead of the current allocation of funds per hectare, subsidies should honour the protection of water, nature, biodiversity. The European Union’s new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive requires firms to prevent risks of pollution, especially when related to human rights abuses. Information campaigns and a requirement to better label the scarcity-weighted water footprint on food packaging are also steps towards sustainable water protection.